Introduction and History

Stickler syndrome is a genetic condition which primarily affects the collagen in the body – a key building block for many of our tissues, like cartilage, joints, eyes, and ears. Because collagen is so widespread, Stickler syndrome can affect many different parts of the body.

The most common problems seen in Stickler syndrome are related to:

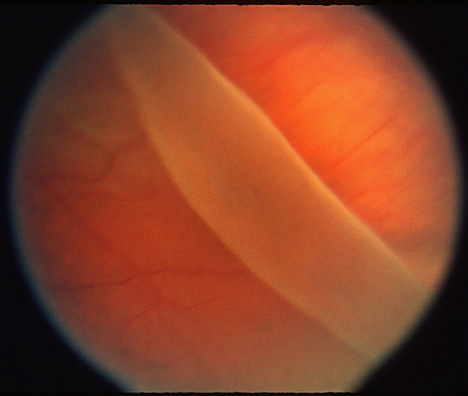

- Eyes: Severe nearsightedness (myopia), problems with the jelly-like substance in the eye (vitreous), retinal detachment (Figure – when the light-sensing part of the eye pulls away), and glaucoma (high eye pressure).

- Joints: Joint pain, stiffness, and sometimes early arthritis, especially in the hips, knees, and ankles.

- Hearing: Hearing loss, which can be mild to severe and may get worse over time.

- Face: Often has a distinctive look, including a flattened mid-face, small nose, and sometimes a smaller-than-average lower jaw. Some babies might be born with a cleft palate (an opening in the roof of the mouth).

This condition was first identified and described in 1965 by Dr. Gunnar Stickler, a doctor at the Mayo Clinic, after he observed a family with many members showing these shared symptoms [1].

Who Is Affected?

Stickler syndrome is considered one of the most common inherited conditions affecting connective tissue; however, it remains relatively rare. It’s estimated to affect about 1 in 7,500 to 1 in 10,000 newborns [2]. It affects males and females equally and is seen in people of all ethnic backgrounds.

Since it’s a genetic condition, if a parent has Stickler syndrome, there’s a 50% chance that each of their children will also inherit the condition [3]. However, the severity of symptoms can vary greatly, even within the same family. One person may experience very mild symptoms, while another family member with the same genetic change may have more severe problems.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Stickler syndrome usually entails identifying the combination of symptoms exhibited. There is no single test that confirms it; instead, it is based on a collection of findings. Doctors will look for:

- Eye exam findings: Such as high nearsightedness, abnormal vitreous gel (which can appear empty or stringy), and signs of retinal problems.

- Hearing tests: To check for any hearing loss.

- Joint examinations: To assess flexibility and any signs of joint pain or early arthritis.

- Facial features: Observing the characteristic facial appearance.

- Family history: Checking if other family members have similar symptoms.

The diagnosis is typically confirmed through genetic testing, which searches for alterations (mutations) in specific genes known to cause Stickler syndrome. The most common genes involved are COL2A1, COL11A1, and COL11A2 [3].

Treatment

There is no cure for Stickler syndrome, but treatments focus on managing the symptoms and preventing complications. A team of specialists usually works together to care for someone with Stickler syndrome, including eye doctors (ophthalmologists), ear doctors (otologists/audiologists), bone and joint doctors (orthopedists), and sometimes geneticists and craniofacial specialists.

- Eye Care:

- Regular Eye Exams: Crucial for early detection of problems like retinal detachment.

- Laser or Freezing Treatment (Cryopexy): Sometimes used as a preventive measure to strengthen the outer edges of the retina in high-risk individuals, though this is debated [4].

- Retinal Detachment Repair: If the retina detaches, surgery (like scleral buckle or vitrectomy) is performed to reattach it. Prompt surgery is crucial for preserving vision [5].

- Glaucoma Management: Medications or surgery may be needed to lower eye pressure if glaucoma develops.

- Cataract Surgery: If cataracts (clouding of the eye’s lens) develop.

- Hearing Care: Regular hearing tests are important. Hearing aids can be very helpful for hearing loss.

- Joint Care: Physical therapy, exercise, pain management, and sometimes surgery (like joint replacement) for severe arthritis.

- Facial/Palate Issues: For babies born with a cleft palate, surgery is performed to repair it.

Prognosis

The prognosis for Stickler syndrome varies widely. Many individuals live full, productive lives, but they often require ongoing medical care to manage their symptoms. With modern medical and surgical advancements, particularly in eye care, the risk of severe vision loss has decreased significantly. Early diagnosis and regular monitoring are key to improving outcomes. While some challenges related to vision, hearing, and joints may be lifelong, proactive management can greatly improve quality of life.

Current Research

- Research on Stickler syndrome continues to advance our understanding of this complex condition:

- Gene Discovery and Function: Scientists are still working to identify all genes involved in Stickler syndrome and understand how their changes lead to the wide range of symptoms. This research can aid in earlier diagnosis and potentially contribute to the development of new treatments.

- Improved Surgical Techniques: Advances in vitreoretinal surgery, particularly for retinal detachment repair, continue to enhance visual outcomes for individuals with Stickler syndrome. Surgical approaches are constantly being refined. For example, Dr. Antonio Capone Jr. has been instrumental in refining surgical techniques for complex retinal detachments, which are often seen in Stickler Syndrome due to the abnormal vitreous [6].

- Pharmacologic Therapies: Currently, there are no specific drugs to treat the underlying collagen defect; however, research is exploring ways to strengthen connective tissues or prevent complications. For instance, studies are exploring whether certain medications might help stabilize the vitreous or prevent early-onset arthritis, although these are still in the early stages [7].

- Natural History Studies: These studies follow individuals with Stickler syndrome over many years to gain a deeper understanding of how the disease progresses in different individuals. This information is crucial for providing more accurate guidance and predicting outcomes [8].

Organizations like the Stickler Syndrome Support Group play a vital role in connecting families and supporting research efforts.

References

- Stickler, G. B., Belau, P. G., Farrell, F. J., Jones, J. D., Pugh, D. G., Kark, A. E., & Power, H. (1965). Hereditary Progressive Arthro-Ophthalmopathy. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 40(6), 433-455.

- Orphanet. (n.d.). Stickler syndrome. Retrieved from https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Disease_Search.php?lng=EN&data_id=649&search=Disease_Search_Simple&Chr=649&diseaseType=Pat&Disease(s)/group%20of%20diseases=Stickler-syndrome

- MedlinePlus. (2018, September 11). Stickler syndrome. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/stickler-syndrome/

- Aaberg, T. M., & Aaberg, T. M. (2018). Prophylactic Therapy for Retinal Detachment in Stickler Syndrome: The Controversy Continues. Retinal Cases & Brief Reports, 12(4), 317-318.

- Trese, M. T., & Capone, A. Jr. (2018). Retinal detachment in Stickler syndrome: management considerations. Retina, 38(10), 1901-1906.

- Kjeldsen, S. S., Bak, M., Henriksen, K., & Pedersen, L. (2022). Exploring Pharmacological Interventions for Collagen-Related Disorders: A Focus on Stickler Syndrome. Cells, 11(13), 2050.

- Sowden, J. C., Houlden, H., & Bitoun, E. (2023). Natural history studies of inherited retinal dystrophies: challenges and opportunities. Eye (London), 37(6), 1081-1087. (This reference discusses natural history studies for inherited retinal dystrophies in general, which would apply to the retinal aspects of Stickler syndrome.)