Introduction and History

Coats’ disease is a rare eye condition where the tiny blood vessels in the retina develop abnormally. The retina is the light-sensitive layer at the back of your eye that acts like the film in a camera, sending visual messages to your brain. In Coats’ disease, these abnormal blood vessels, called “telangiectasias” (tel-AN-jee-ek-TAY-shuhs), can leak fluid, blood, and fatty material (exudates) into and under the retina.

This leakage can cause the retina to swell and may lead to a separation of the retina from the back of the eye, known as a retinal detachment. These changes can cause vision loss, ranging from mild to severe. Coats’ disease almost always affects only one eye and is not usually passed down in families (it’s typically not hereditary).

Coats’ disease is named after a Scottish eye doctor, Dr. George Coats, who first described the condition in detail in 1908. He identified it as a specific problem with the retinal blood vessels leading to exudation, primarily in young males.

Who Is Affected?

Coats’ disease is most commonly found in young males, with about 3 out of 4 people diagnosed being male. While it can occur at any age, it is usually diagnosed in childhood, often before the age of 10. In most cases (around 95%), only one eye is affected. Because it’s not usually an inherited condition, it typically happens sporadically, meaning it occurs by chance and isn’t passed from parents to children.

Diagnosis

The first signs of Coats’ disease can include:

- Leukocoria: A white or yellowish reflection in the pupil when light is shone into the eye (like in a photograph taken with a flash). This is a serious sign that needs immediate medical attention.

- Strabismus: Crossed eyes or an eye that wanders.

- Poor vision in one eye, which a child might not complain about.

- Sometimes, it’s found during a routine eye exam or school vision screening.

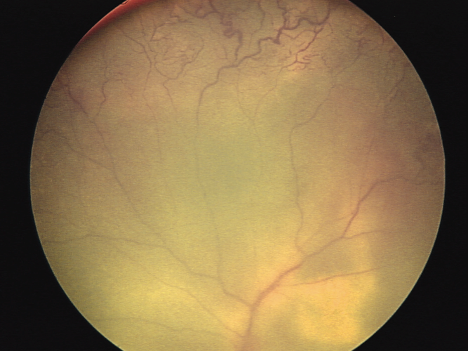

An ophthalmologist (eye doctor), particularly a retina specialist, will perform a dilated eye exam to look at the back of the eye. They will look for the tell-tale signs of abnormal, leaky blood vessels and exudates (Figure).

Other tests may include:

- Fluorescein angiography: A special dye is injected into an arm vein, and pictures are taken as it flows through the retinal blood vessels. This helps highlight leaky areas.

- Ultrasound: Sound waves are used to create an image of the inside of the eye, especially if the view of the retina is blocked by fluid or a cataract.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): This scan provides detailed cross-sectional images of the retina, showing swelling and fluid.

It’s essential to diagnose Coats’ disease correctly because leukocoria can also be a sign of a serious eye cancer called retinoblastoma.

Treatment

The primary goal of treatment is to seal the leaky blood vessels and prevent fluid and exudate from damaging the retina, and to reattach the retina if it has detached. Treatment depends on how severe the disease is:

- Observation: Very mild cases may only need careful monitoring.

- Laser Photocoagulation: A laser is used to heat and destroy the abnormal blood vessels to stop them from leaking. This is often used for earlier stages.

- Cryotherapy: This treatment uses extreme cold to freeze and destroy the abnormal vessels. It’s often used when the leaky vessels are in the far periphery (edges) of the retina or if there is a lot of fluid.

- Anti-VEGF Injections: Medications called anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) drugs can be injected into the eye. These drugs help reduce the growth of abnormal blood vessels and decrease leakage. Sometimes steroids are also injected to reduce inflammation and leakage.

Surgery (Vitreoretinal surgery): If the retina has detached extensively, or if there is significant bleeding into the vitreous (the gel-like substance that fills the eye), surgery may be needed. This can involve procedures like a vitrectomy (removing the vitreous gel) and/or a scleral buckle (placing a supportive band around the eye).

Prognosis

The outlook for Coats’ disease varies greatly depending on how early it’s diagnosed and treated, and how severe it is. With early and effective treatment, vision can often be stabilized, and in some cases, improved. However, some vision loss is common, especially if the macula (the central part of the retina responsible for sharp vision) is affected. In severe, untreated cases, Coats’ disease can lead to total retinal detachment, blindness, and sometimes even the need to remove the eye (enucleation) if it becomes painful due to high pressure (glaucoma). Lifelong follow-up is essential.

Current Research

Research in Coats’ disease is focused on several areas:

- Understanding the Cause: Although the exact cause of Coats’ disease is still unknown in most cases, researchers are investigating potential genetic factors or other triggers that may lead to abnormal blood vessel development. Though classic Coats’ is sporadic, very rare conditions like “Coats plus syndrome” have known genetic causes, and some research looks into genes like NDP that are involved in eye development.

- Improving Treatments: Studies are ongoing to determine the optimal use of current treatments, such as laser, cryotherapy, and anti-VEGF drugs, including when to administer them and in what combinations, to achieve the best results and preserve vision. New drugs and delivery methods are also being explored.

- Long-term Outcomes: Researchers are studying the long-term effects of Coats’ disease and its treatments to better predict outcomes and manage any late complications. Large collaborative studies are helping to gather more information on this rare disease.

References

- Coats, G. (1908). Forms of retinal disease with massive exudation. Royal London Ophthalmic Hospital Reports, 17(3), 440–525.

- https://www.orpha.net/en/disease/detail/190 (Coats disease)

- Rao P, Knapp AN, Todorich B, Drenser KA, Trese MT, Capone A Jr. (2019) Anatomical Surgical Outcomes of Patients With Advanced Coats Disease and Coats-Like Detachments: Review of Literature, Novel Surgical Technique, and Subset Analysis in Patients With Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy. 2019 Oct:39 Suppl 1:S182-S190.

- Darst, S., Gantois, G., Chu, Z., Zhou, X., Ang, M., Chen, K. C., Ancona-Lezama, D., Arrigo, A., Battaglia Parodi, M., Krivosic, V., Pearce, I., Querques, G., Staurenghi, G., Steel, D., Tadayoni, R., Abreu-Gonzalez, R., Adan, A., Arevalo, J. F., Arruti, N., Audren, F., … Capone, A. Jr., … & Yoon, Y. H. (2024). Clinical Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes in Unilateral Coats disease – a Global Collaborative Study. Ophthalmology Retina. (Published online ahead of print, article in press, reflecting recent research as of late 2024/early 2025).

The characteristic vascular changes of Coats Disease are seen in the upper part of the retinal image. Whitish subretinal lipid is seen in the lower right.